Not long ago there was little question that the essential object of the marriage consent corresponded to its primary end, universally held to be the procreation and education of children. Accordingly, marriage consent was understood to consist in an assent to those acts conducive to this end. The 1917 Code of Canon Law was explicit in this matter, describing matrimonial consent as “an act of the will by which each party gives and accepts a perpetual and exclusive right over the body, for the acts which are of themselves suitable for the generation of children.” (Code of Canon Law, 1917, Can. 1081, 2., emphasis added) This right over the body, or in the traditional terminology the ius in corpus, was given by both husband and wife and therefore was held to entail the mutual obligations of each to each, the obligations by which they are exclusively and perpetually bound.

Despite the fact that this was the long-standing position of the Church, during the first half of the Twentieth Century Catholic theologians began to reevaluate the traditional emphasis on procreation in the Church’s understanding of marriage. Most notable were Dietrich von Hildebrand, Herbert Doms, and Bernhardin Krempel, C.P. These three wrote influential works on marriage rejecting the traditional emphasis on procreation as the primary end of marriage, an emphasis which they believed diminished the more personal or interpersonal values of marriage. These are the values such as the conjugal love between the partners and their mutual fulfillment and satisfaction, realized in their life-companionship or community of life. Though both von Hildebrand and Doms accepted procreation as an essential end of marriage, and von Hildebrand did not reject it as the primary end, they both made efforts to distinguish the meaning and inherent value of marriage from its end or purpose. Doms, however, went so far as to state that “there can no longer be sufficient reason…for speaking of procreation as the primary purpose (in the sense that St. Thomas used the phrase) and for dividing off the other purposes as secondary.” (Herbert Doms, The Meaning of Marriage) Krempel carried out his line of reasoning even further. He argued first that marriage as a category of relation entails a mutual possession, “not merely of another’s sexual faculties but of another’s entire person as sexually differentiated.” As this relation involves the entire person, Krempel rejected what he considered to be the narrow conception of ius in corpus in favor of a ius in personam, or a “right to the person.” The end result of his reasoning was to explicitly deny procreation as the primary purpose of marriage while affirming a “union of lives” as its only essential end. (John C. Ford, S.J., and Gerald Kelly, S.J., Contemporary Moral Theology, vol. 2, pp. 26-27)

Yet, despite the traditional emphasis on the procreative ends of marriage, the personal values emphasized by these thinkers had not been overlooked or disregarded by the teaching Magisterium of the Church. Pius XI, for example, in his 1930 Encyclical on Christian Marriage, Casti connubii, writes eloquently on the love of husband and wife, calling it a “deep attachment of the heart” which he says holds “pride of place” and should pervade the whole of married life. Conjugal love, he explains, must go beyond mere help, with the mutual formation and perfection of husband and wife as its principal purpose:

“This mutual molding of husband and wife, this determined effort to perfect each other, can in a very real sense, as the Roman Catechism teaches, be said to be the chief reason and purpose of matrimony, provided matrimony be looked at not in the restricted sense as instituted for the proper conception and education of the child, but more widely as the blending of life as a whole and the mutual interchange and sharing thereof.” (Pius XI, Casti connubii, 24.)

Given such expressions, perhaps it is not surprising that both Doms and Krempel, whose writings on marriage followed the promulgation of Casti connubii, sought to use the Encyclical as magisterial validation to their personalist claims and variances from the traditional understanding of the nature and ends of marriage. Krempel actually saw his work on marriage as a commentary on the very passage quoted above. And yet this statement of Pius XI is more properly interpreted as a simple acknowledgment that moral perfection is the chief good and end of all men, regardless of vocation. It is, therefore, the ultimate end of any love, conjugal or otherwise, which always seeks the good of the beloved. Immediately preceding this passage, in fact, Pius XI speaks of that holiness which all men have as their end, “all men of every condition, in whatever honorable walk of life they may be.” (Casti connubii, no. 23.) When Pius XI speaks, then, of the “mutual molding of husband and wife” he is referring principally to growth in holiness; and while holiness or interior perfection is the ultimate end of all human associations, including marriage, it is not the specific difference or defining characteristic of marriage, qua marriage, nor its primary end, which the text of the Encyclical makes clear.

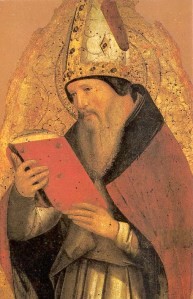

Casti connubii is structured around what is known as the “three goods of marriage,” the bona matrimonii. This is a schema first articulated by St. Augustine and subsequently integrated within the common tradition of Catholic theology on marriage, including St. Thomas Aquinas. One of the three goods is identified as the good of the sacrament. This good denotes “both the indissolubility of the bond and the raising and hallowing of the contract by Christ Himself, whereby He made it an efficacious sign of grace.” (Casti connubii, no. 31) As with all sacraments, the sacrament of marriage is ultimately ordered to sanctification, again, the ultimate end of all, married and unmarried alike. Another good of marriage identified by St. Augustine and reaffirmed in Casti connubii is the good of conjugal fidelity. Conjugal fidelity in this context is rightfully understood as a property of conjugal love, which, as already mentioned, Pius XI says “should inform and pervade all of the duties of married life.” But the chief emphasis of the Encyclical is on the good of children, underscored in Casti connubii as the primary good, the good which holds the “first place” amongst all the possible goods of the matrimonial bond. Thus, contrary to the uses to which the Encyclical was put by the Catholic personalists, Casti connubii reaffirms the traditional understanding of marriage as an institution ordered primarily to the generation and education of children, with indissolubility and fidelity included as essential goods.

Casti connubii is structured around what is known as the “three goods of marriage,” the bona matrimonii. This is a schema first articulated by St. Augustine and subsequently integrated within the common tradition of Catholic theology on marriage, including St. Thomas Aquinas. One of the three goods is identified as the good of the sacrament. This good denotes “both the indissolubility of the bond and the raising and hallowing of the contract by Christ Himself, whereby He made it an efficacious sign of grace.” (Casti connubii, no. 31) As with all sacraments, the sacrament of marriage is ultimately ordered to sanctification, again, the ultimate end of all, married and unmarried alike. Another good of marriage identified by St. Augustine and reaffirmed in Casti connubii is the good of conjugal fidelity. Conjugal fidelity in this context is rightfully understood as a property of conjugal love, which, as already mentioned, Pius XI says “should inform and pervade all of the duties of married life.” But the chief emphasis of the Encyclical is on the good of children, underscored in Casti connubii as the primary good, the good which holds the “first place” amongst all the possible goods of the matrimonial bond. Thus, contrary to the uses to which the Encyclical was put by the Catholic personalists, Casti connubii reaffirms the traditional understanding of marriage as an institution ordered primarily to the generation and education of children, with indissolubility and fidelity included as essential goods.

The traditional understanding and ordering of the ends of marriage were reinforced in a formal decree of the Holy Office under Pius XII in 1944. (AAS, 36, 1944) This decree was directed specifically to what it called “a new departure in thought and speech” concerning the ends of marriage. While it did not mention them specifically, it was implicitly understood to be directed to the “personalist” theologians such as Doms and Dr. Krempel, among others. In that decree, it is unequivocally affirmed that the procreative end of marriage is primary, while its secondary ends are not “equally principle and independent” but are “essentially subordinate to the primary end.”

Pius XII reiterated this teaching on various occasions, including in his Allocution to Midwives in 1951. There he draws upon “Christian tradition” and “what the Supreme Pontiffs have repeatedly taught” to affirm the primacy in marriage of the generation and education of children, above and beyond any personal good of the spouses:

“…the truth is that matrimony, as an institution of nature, in virtue of the Creator’s will, has not as a primary and intimate end the personal perfection of the married couple but the procreation and the upbringing of a new life. The other ends, inasmuch as they are intended by nature, are not equally primary, much less superior to the primary end, but are essentially subordinated to it. This is true of every marriage, even if no offspring result, just as of every eye it can be said that it is destined and formed to see, even if, in abnormal cases arising from special internal and external conditions, it will never be possible to achieve visual perception.” (Allocution to Midwives,1951)

None of this should be taken to imply, of course, that the personal good of the spouses is unimportant, or that marriage is of no value aside from its procreative ends. However, Pius XII makes it clear that the personal or interpersonal goods of marriage are essentially subordinate to its procreative end, and are “included in the ambit of the specific function of husband and wife, which is to be authors and educators of a new life.” This is but to echo the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, who maintained that the secondary ends of marriage are included in its principle end, procreation, for this end “signifies not only the begetting of children, but also their education, to which as its end is directed the entire communion of works that exists between man and wife.” (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Supplement, q.49, a.2, ad 1, emphasis added)

Examples could easily be multiplied, but it is fairly clear what the Church has taught regarding the nature of marriage, from St. Augustine to St. Thomas Aquinas to Pope Pius XII: Marriage is an institution both human and divine, ordered primarily to the procreation and education of children, involving a life in common. While there are other important goods attached to this life in common of both a personal and a social nature, these can be obtained in other human relationships and are therefore not exclusive to marriage. For that reason, they cannot be identified as defining marriage in its essence. What distinguishes marriage in its essence, its specific difference, if you will, is the ius in corpus, the right to those acts that by their nature are ordered to the generation of children. Hence it was held throughout the centuries that it is the exchange of this right that comprises the essence of marital consent.

The Evolution in the Understanding of Marriage Following Vatican II

However, that was before Vatican II. Since then, the canonical community, especially in America, has sought to modernize Church teaching with the assumption that we follow a more enlightened path by shifting the emphasis of marriage away from its procreative end. Accordingly, despite the clear teachings of past popes, councils, and saints of the Church, modern canonists have drawn upon brief characterizations of marriage in Gaudium et spes to re-define marriage to include its more personal elements in its very essence, equal to if not superior to the ius in corpus. The nature of this expanded, re-definition of marriage is nowhere more clearly expressed than in the writings of the influential American canonist, Lawrence G. Wrenn, who writes:

“…until the 1960’s, the essence of marriage was considered to be the right to the joining of bodies, or more specifically, the right to those acts which are per se for the generation of offspring.”

“Since the late 60’s…the essence of marriage has been expanded to include what may be called the right to the joining of souls, i.e., the right to spousal communion, a community of life….”

“[inclusion of]…the personal element as well as the physical element was immediately precipitated by…Gaudium et spes, which defined marriage as an “intimate partnership of life and love” in which “the partners mutually surrender themselves to each other”…and also by the encyclical letter Humanae Vitae which said, “through the mutual giving of themselves…the spouses seek to attain that communion of persons, by which they perfect one another.” (Lawrence G. Wrenn, Divorce and Remarriage in the Catholic Church.)

Now there is no problem with calling marriage “a joining of souls” or, for that matter, “a communion of persons,” or “an intimate partnership of life and love.” Such poetic characterizations are beautiful and heartwarming and no doubt contain a degree of truth. (Such expressions are really not unique to the post-Vatican II enlightenment. Thus we can find Pius XI describing marriage thirty years before the Council as “a union of souls” in which “the contracting parties are joined and knit together more directly and more intimately than are their bodies.”) The problem arises when we try to incorporate such nebulous concepts into the specific essence of marriage, or try to imbue them with rights and a juridic content. We would do well here to consider that not everything said about marriage is necessarily an expression of its essence. One may hope in a marriage to form a communion of persons or to join their soul to another, whatever these notions might mean. Yet such notions may just as well be predicated of other human relationships, even relationships proscribed by the moral teaching of the Church. They therefore cannot express the essence of Christian marriage per se, however desirable such communion of persons or souls may be.

Furthermore, we cannot simply ignore the discrepancy between this new expanded concept of marriage and the prior historical understanding, the understanding that was embodied in the 1917 Code of Canon Law in its elaboration of matrimonial consent as “an act of the will by which each party gives and accepts a perpetual and exclusive right over the body, for the acts which are of themselves suitable for the generation of children.” This was the understanding that existed in the Church for millennia, and it is difficult to believe that the Church had the requirements for marriage wrong for all this time and that we are just now getting it right. Nor can we dismiss this discrepancy by saying that the change is simply a development of Catholic teaching and not a rejection of prior teaching, for the prior teaching was that the perpetual and exclusive right over the body, the ius in corpus, is the sole object of the marriage vow. The fact that the new interpretation includes the ius in corpus in addition to the expanded element does not resolve the difficulty. One may come out with an expansion of the Trinity to include another person, but he cannot claim this to be a simple development just because he includes the previous three.

On the other hand, there is also a clear advantage of adopting an expanded notion of the essence of marriage and thereby an expanded object of matrimonial consent. That advantage is that it gives to diocesan tribunals much greater leeway in ruling that a marriage is void if it can be determined that a spouse did not understand or was not capable of forming a communion of persons or was unable to join his soul to another. Accordingly, we have seen an explosion of annulments throughout the American tribunal system. In the early 60s, declarations of nullity in the United States came in at around 300 per year. Since the late 60’s (when, according to Wrenn, we expanded the essence of marriage to include the right to a “joining of souls” and the right to “spousal communion”) the number of such declarations reached over 60,000 in 1991 alone. (Edward Peters, “Annulments in America: keeping bad news in context”, Homiletic & Pastoral Review (Nov 1996) 58-66.)